Outer space and the future are the two most overused settings in science fiction—and that’s because they’re such a gosh darn fun playground. There’s nothing more freeing as a writer than having the entire universe and all of time as your sandbox. Complete creative freedom.

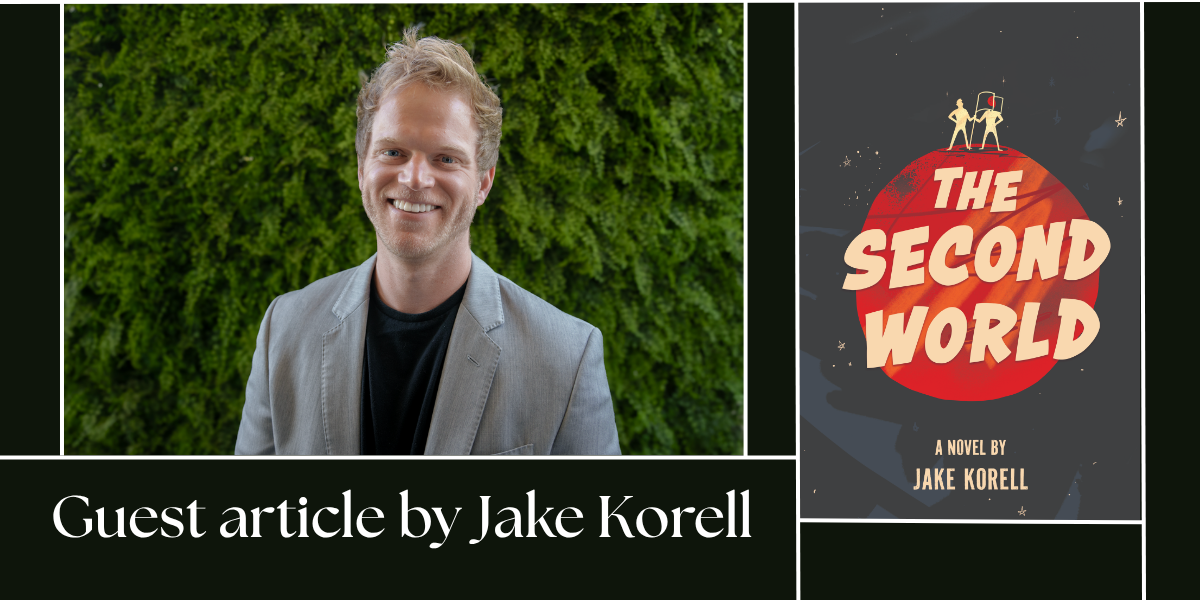

And I’ve always been drawn to building my sandcastles in the near future, where the technology is advanced enough to be imaginative but the world is familiar enough to relate to. Societal and historical references don’t feel out of place. Mars offers the same sweet spot: it’s otherworldly, but still our next-door neighbor—relatively. And in real life, we’re only decades away from sending humans there, which makes it plausible enough to feel real. The Red Planet was the perfect setting for my debut novel The Second World.

I didn’t set out to write a political satire. It just sort of happened—if you count writing dozens of terrible drafts before landing on one version you don’t hate as something “just happening.” What hooked me early on was the idea of a Mars colony developing its own governance, because entirely new nations don’t really pop up on Earth anymore. All the land’s spoken for. And the more I thought about it, the more I realized how naturally a Martian colony mirrors the thirteen American ones. Outer space is just a much bigger Atlantic Ocean. Add “space” in front of “ship,” and you’re sailing to the “New World.”

From there, I became obsessed with the idea of history repeating itself. The project actually started as a pilot for an adult animated series that was a satire of the American Revolution, with plans for later seasons to echo other eras of U.S. history. When I turned it into a novel, I had the room to explore everything from independence to the Space Race. (I think most authors would’ve split it into a trilogy given the scope, but my attention span isn’t what it used to be. Plus, comedy is brevity!)

That’s when the major world-building ramped up. Every historical detail got twisted for Mars and sci-fi absurdity: guerilla warfare became gorilla warfare, Nazis became robots, Native Americans became Native Martians—aliens living underground. At first, everything was on the nose, deliberately so. That was part of the humor. But I eventually realized that if I wanted to keep readers engaged, the book couldn’t just be a parody of America for 400-plus pages. That would get very old, very fast. A crystal-clear reflection in a mirror isn’t nearly as interesting as a reflection in a pond. The image is hazier, distorted. It’s recognizable, but different—and the real fun happens when you create ripples and morph the image into something new. Mars needed to develop as a separate world, with its own culture and contradictions.

That extra breathing room allowed the historical satire to deepen into political satire. The parallels to American history became the scaffolding. The story structure was held up by the past, but the tone and themes were undeniably modern. Suddenly I was writing about nationalism, media, and culture.

Still, the early drafts read like a history textbook with punchlines. The world felt clever but cold. I like to think I’m pretty funny, but I knew my jokes couldn’t sustain an entire book. I had created an interesting world, but the readers needed to care about the people living in it. That’s when I borrowed a father-son dynamic from another project I’d shelved—a self-absorbed, pompous father and his angsty, irreverent son.

Their relationship gave the story emotional gravity—the personal became the political, and vice versa. The father became the epitome of a Baby Boomer: hell-bent on success and legacy, while criticizing the younger generation for lacking the same values, failing to realize those values no longer fit the world the older generation shaped. The son became the voice of a generation living through “once-in-a-lifetime” events on a monthly basis, numb to the broken systems, resorting to apathetic posts about injustice on social media and calling it “activism.”

Through their conflict, I could explore not just the farce of politics, but the exhaustion of existing inside it. That tension opened everything up: the satire of history and politics became one about generational divides. The son’s father became the “Founding Father” of Mars, giving me the perfect lens to explore the disillusionment of Millennials and Gen Z.

My humor is an unpretentious crockpot of dark comedy, observant irreverence, and parody with empathy. It’s easy to exaggerate the ridiculousness of our world—especially with the freedom of a near-future, outer-space setting—but what makes the story work is that it’s still grounded in human messiness. People still want to be seen, to matter, to understand their self-worth.

That balance of humor and humanity is at the heart of The Second World. Beneath the aliens, clones, and hee-haws of a space donkey, it’s really a story about purpose and legacy—what it means to build something new while living a finite life in an infinite universe. Satire just lets me sneak that question in disguised as a joke. My hope is that readers laugh, then cry, then maybe do a little bit of both at the same time.

Writing the book reminded me that no matter how far away you set your story—through distance or time—it’ll still be a story about humanity in one form or another. And hopefully, one with plenty of laughs.

By Jake Korell

About the writer

JAKE KORELL’s voice and sense of humor have been shaped by a cast of hilariously

unforgettable friends and family, and by his serious, deeply held conviction that life shouldn’t be

taken too seriously—or held with such deep conviction. He lives in Los Angeles with his partner,

McCauley, and their dog, Dewey, and never misses a Martini Monday.

About Jake Korell’s debut novel, The Second World – coming soon!

Mars has declared its independence from Earth. But building a country takes more than a new flag, an arena-worthy anthem, and naming Pluto the donkey the national animal. As the Red Planet spirals into political upheaval, Flip Buchanan—the irreverent, reluctant son of the most powerful man on Mars—stumbles through two tumultuous decades of alien discoveries, killer clones, and the chaos of a new nation still working out the kinks.

Always second-best in a family obsessed with being first, Flip must grapple with the absurdity of Martian society and the gravity of legacy to step out of his father’s shadow and define self-worth on his own terms—a feat that can feel as impossible as climbing Olympus Mons.

For fans of Andy Weir and Kurt Vonnegut, this satirical coming-of-age space epic blends sharp wit, surprising emotional depth, and bold world-building. Equal parts hilarious and heartfelt, The Second World navigates found family, generational divides, and the outrageous struggle to make your finite life matter in an infinite universe—with poignant reflections on power, sensationalized media, and fractured culture.

Leave a Reply